This February I read CHIP WAR by Chris Miller. The book follows the semiconductor industry form the invention of the transistor, to the trade war between the USA and China. The book is mainly about the economics of electronics manufacturing and geopolitics, but has some technological insight nuggets. I highly recommend it.

Below some notes and things I learned.

There’s also a discussion on Twitter.

The Formula is Abundance

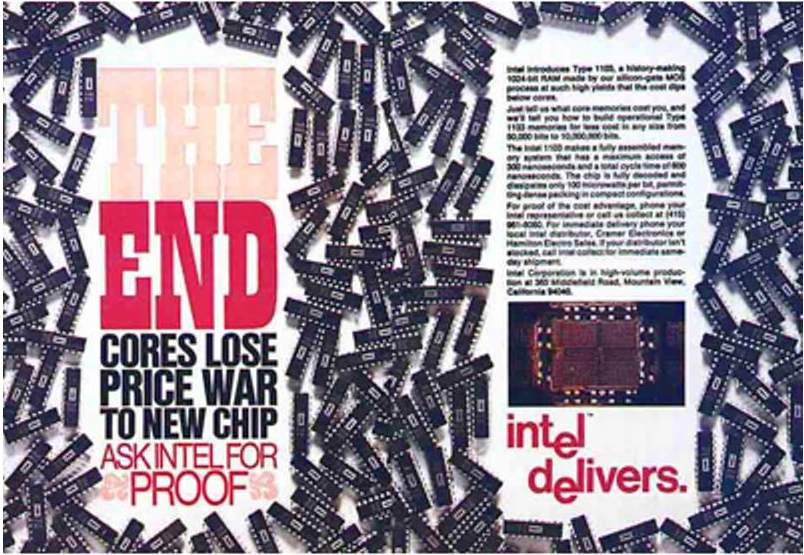

Aggressive price-cutting of ICs was a deliberate Fairchild strategy to bootstrap a consumer market. This was a deliberate choice, and not an obvious one to make, given the abundance of demand in DoD funding. It definitely wasn’t Bill Shockley‘s choice in his own company.

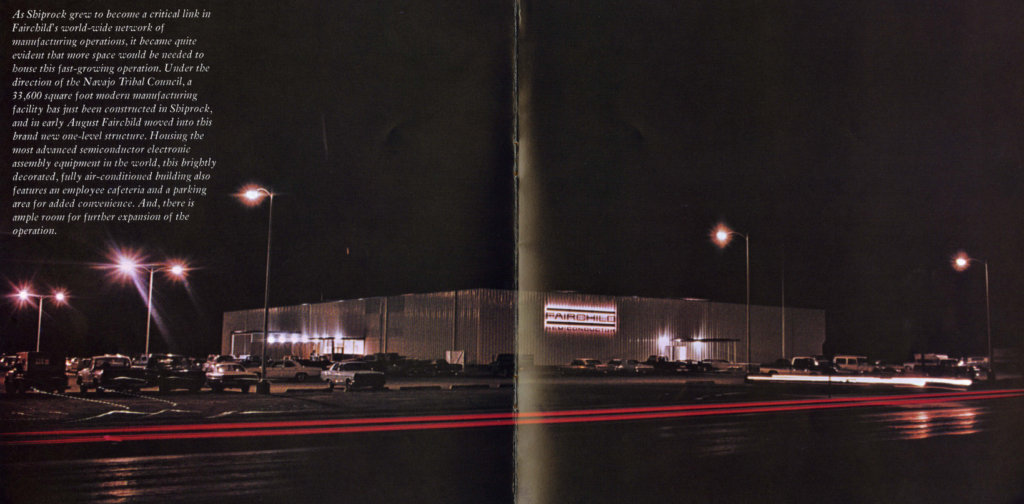

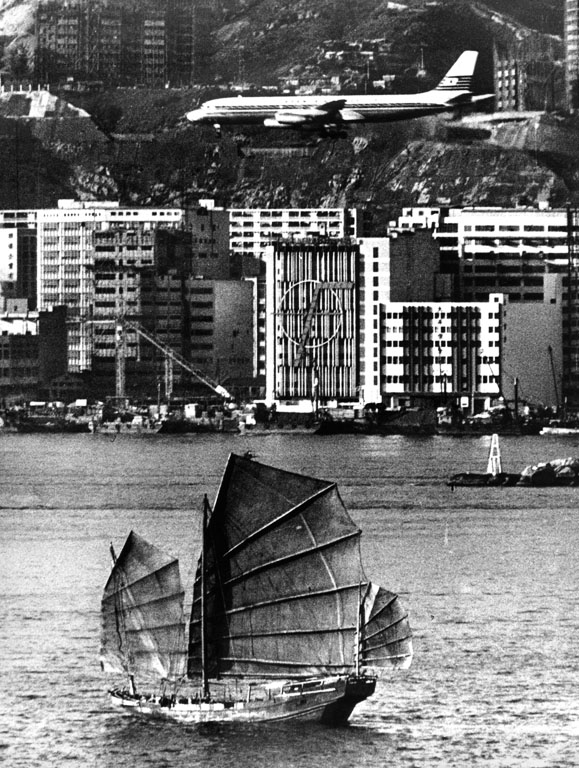

Although accepting DoD contracts, Fairchild Semiconductor was keeping defense-related development at an arm’s length. Had they leaned into being a military contractor, development would not be incentivized to happen fast or cheap. Instead, they kept looking for consumer applications and opened factories wherever was cheapest. Fairchild opened a plant in Shiprock, NM in 1969 (employing primarily Navajo Women) for DoD business and a plant in Hong Kong for TV & Radio parts.

In both cases, factories brought rural communities into tech work (still low-wage manual labor). Later in Southeast Asia, this formula repeated, as semiconductor factories seeking lower margins increased subsistence farmer intake, and in turn promoting urbanization.

Comparing the US market (in which Fairchild was the only profitable player in the 60s) to other semiconductor efforts, the obvious takeaway is cost-cutting and a large market enabled faster technological growth.

Japan’s Success: The Best Outcome for the US

Japan becoming a consumer electronics empire was an insanely successful US foreign policy move that survived multiple governments and regime changes; Taiwan’s strategy to fill the same role has been its’ biggest growth engine too.

Side note: with Israel’s current state (gestures vaguely at everything going on in 2023), one might forget that it also tried to have the same geopolitical moat in the early 90s with Tower Semiconductor (ex-National Semi, later Jazz Semi) and later Intel’s fabs. It only worked because of a massive Soviet Jew influx; The only hi-tech manufacturing to exist substantially before that was military – a big change came after the 1987 axing of the Lavi jet fighter, which coincided with the Soviet Jew immigration, and flooded the market with skilled engineers. Although there are fabs in Israel, it currently concentrates foundry-model design centers more than a manufacturing center. There are fabs (3 Intel fabs, currently), but Tower-Jazz (2 fabs in Israel) now makes high-precision CMOS sensors and other high-end products more robust against supply chain disruptions.

Morris Chang‘s prediction that supply chain conditions are unique in the East is still undefeated.

Core Knowledge: Word of Mouth

The main driver of US wafer industry was practical experience passed by word of mouth:

- Know-how was colocated, often undocumented.

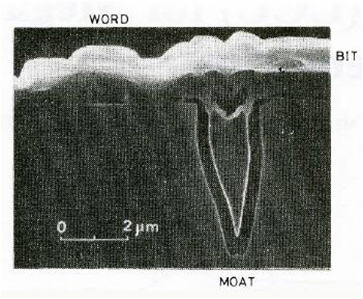

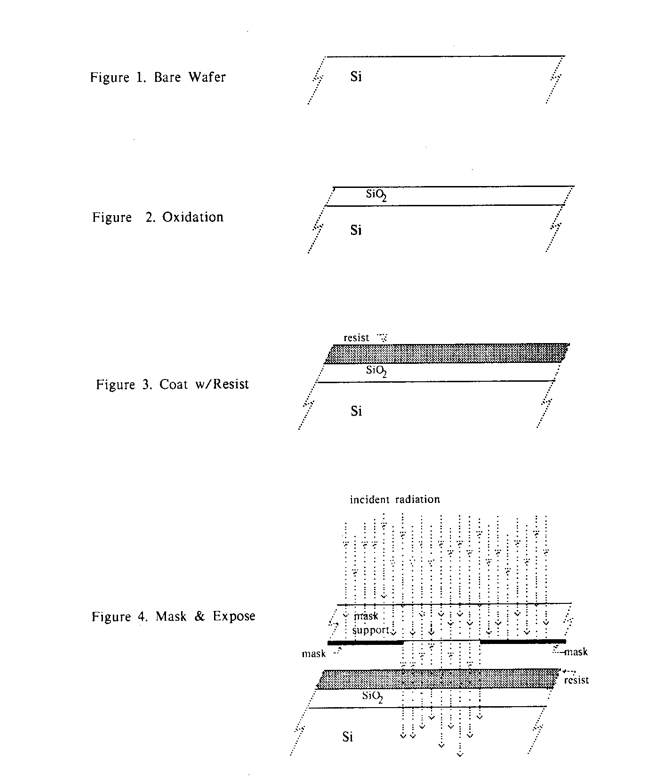

- Majority of know-how was not theory, but engineering: melting temperatures, photoresist exposure times.

- No noncompetes preventing spread of knowledge.

In the 1980s, this knowledge leaked to Japan quickly (legitimately through academic exchange and some notorious industrial espionage cases). Japan’s strategy wasn’t word of mouth: all semiconductor manufacturers were part of a consortium, working together to deepen Japanese dominance in semiconductor manufacturing.

The Semiconductor Industry, as we know it, is a Supply Chain

A robust supply chain has always been a success enabler – not just today, even when things were smaller: it’s hard to imagine that there was a lot less stuff in the world. The USSR could source machinery and components, but hit a wall as soon as its’ process wasn’t good enough: a single supplier won’t improve their yield or cost without real competition. For comparison, when TI needed purer chemicals or sharper lithography masks than the market had, they made them in-house, as a competitive move. In a planned economy, that was harder to do.

This also emphasizes the lack of “miracle” in the evolution of the semiconductor market: The USSR was “constantly 5 years behind” by artificial efforts to catch up – but it never had a scale market.

Morris Chang in the past warned multiple times that the supply chain Southeast Asia has (due to globalization) is unbeatable. Recently he changed his tune, coincidentally speaking at a fab groundbreaking in Arizona:

“Twenty-seven years have passed and [the semiconductor industry] witnessed a big change in the world, a big geopolitical situation change in the world.

Morris Chang

Globalization is almost dead and free trade is almost dead. A lot of people still wish they would come back, but I don’t think they will be back.”

This is also ruffling feathers in Southeast Asia, where TSMC’s efficient supply chain can’t all move elsewhere, definitely not to Europe and US.

Do We Have to Move to the US?

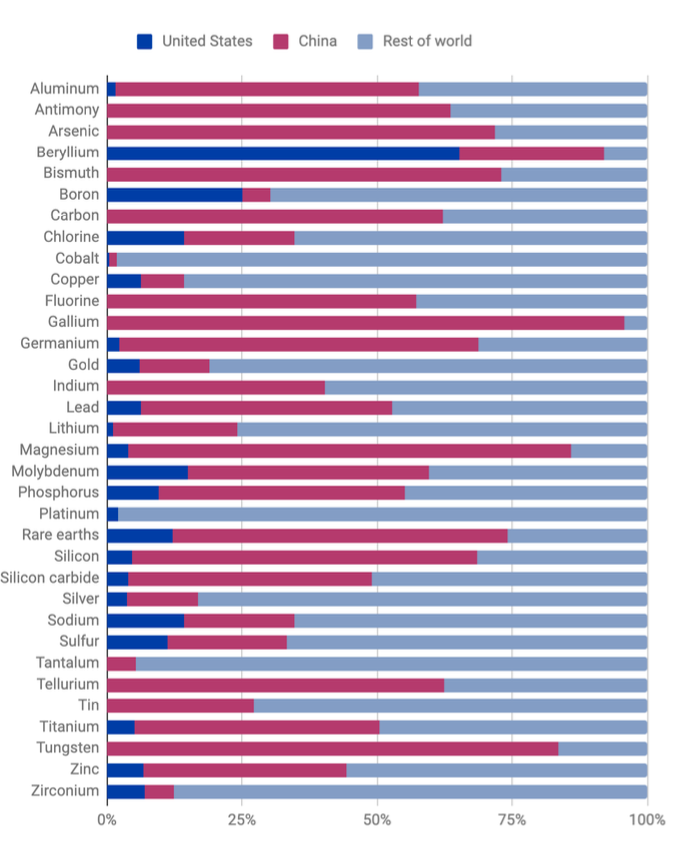

The US is obsessed with tracking and analyzing the semiconductor supply chain. Detaching countries that the US views as threats from the supply chain is really difficult – but so is keeping tabs on every chemical process at risk due to shortage. The discourse forces players in the market to address this publicly. TSMC releases some press material (for public opinion management? not sure) and does publish some reports on their critical sources (I have less than zero expertise on this, mind you).

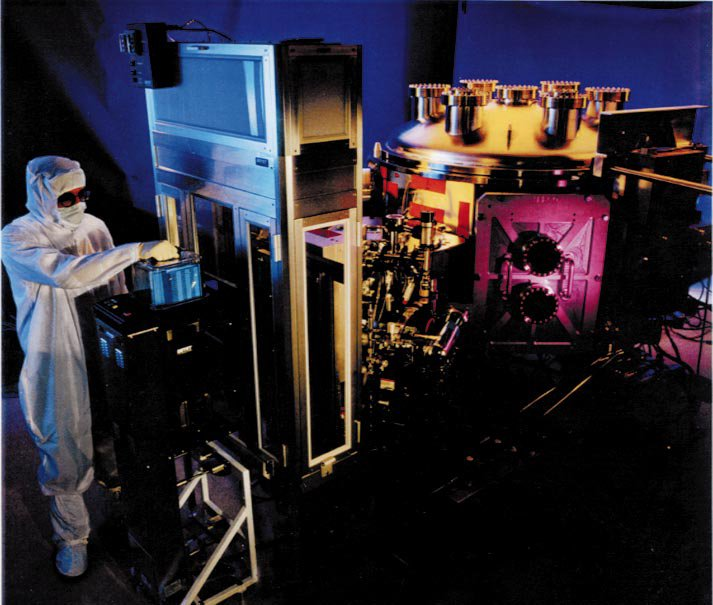

A Western[-ized] fab ecosystem may happen now that a full-on semiconductor war is on with China. CHIP WAR says ASML’s supply chain is the real cause: it’s got thousands of ad-hoc parts sourced from single suppliers. If ASML machines (hella expensive, require ASML technician onsite) are blocked from entering countries the US views as rivals, those countries won’t have access to Extreme UV Lithography for a while (it took the US around 2 decades and multiple nations from research to production).

On the other hand: in the US, unit economics will be pricier, meaning fab margins may suffer – which can lead to many side effects. As I’m writing this, Apple is reportedly lowering the expected production quota of Vision Pro due to Micro OLED panel yield – a technology that’s so far been a challenge to produce consistently. The US hasn’t shown any manufacturing edge yet (Noah Smith has a nice piece on this), and constraining supply channels may be a short-term challenge.

The CDMA/UMTS/5G lineage is the same story of Western strategic importance that x86 and ARM are. Foreign SIGINT code running inside western infra isn’t the only issue, efforts to harm channel capacity happen on simple crappy wifi routers. RF and network safety is an unfortunate frontier – it’s wholly unsexy, but unlikely to go away from defense requirements.